REVIEW BY PADDY WALSH

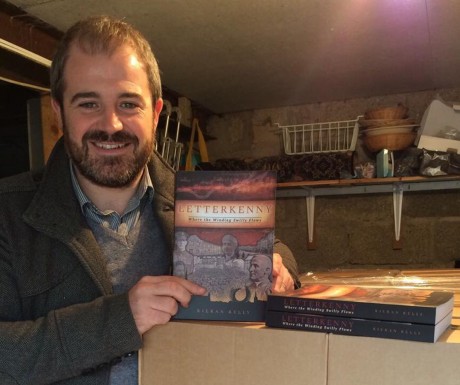

ACCORDING to the census figures of the time, in 1659, the population of Letterkenny stood at the grand total of seventy-three. Kieran Kelly, author and researcher of ‘Where the Winding Swilly Flows’ – a compelling and comprehensive history of his home town which will be launched next week at An Grianán Theatre – doesn’t quite list their names but you feel that had he the resources to do so he would have.

For here is history as it should be – as it should have been when many of us sat at ink-stained desks attempting to distinguish this battle from that and that event from this.

From an acorn of an idea that took shape in 2007 to an oak tree of a publication, the Letterkenny man, aided considerably by the pamphlets and papers of fellow historians and seven years of time-consuming research, has undoubtedly written the definitive history of his home town.

He has delved deep into records and registrars and newspapers and other publications and from his meticulous research through libraries and legends, he has come up with a history that will, for generations to come and the generations after those, provide an illuminating account of how Letterkenny sprang from a small market town into the thriving centre it is today.

Some of this history has been documented over the past few centuries but the author has unearthed a rich selection of anecdotes and ‘Did You Knows’ that are both informative and entertaining and slot in comfortably with the main body of his work.

The author has broken the history into an introduction and twenty chapters focusing on its early development up to the present day.

And he doesn’t even stop there for lurking in the back pages is a complete chronology of what has gone before and a series of Appendixes including a poem depicting the heroic death of Godfrey O’Donnell; a descriptive passage on Letterkenny and Sir George Marbury – founder of the town – written by one Robert Cartwright back in 1625; and a listing of names of various gentry, clerical and business people from 1824.

And rolling back the years further, we have a list of the Hearth Money Rolls dating to 1665. The what, you might rightly ask? Apparently, in that specific year, an Act of Parliament decreed that all those households with hearths (fireplaces and stoves and so forth) had to pay a tax where money was collected in the parish of Conwal.

Kieran Kelly has managed to get his hands on a list of all those in Letterkenny and surrounding areas – 138 in all – who had to bear the heat of this particular tax (who knows, some future historian may draft out in generations to come the names of those who splashed out on their water charges in 2015). Those hearth tax names include, for example, John Stewart of Breachy, Allex m’Niaght of Ellestrin, Daniel Longe of Glencar, Quantein Black of Conwall, Adam Wilson of Tullygay, and Henry m’Davett of Stakernagh.

The author stresses that to him, Letterkenny is not about its buildings – though the main structures are given due prominence here as you’d expect – but about its people. And pages weigh with the names of the people who helped – or perhaps on the odd occasion hindered – make Letterkenny what it is today.

And whether it was on a battle field or a football pitch, a political platform or a theatrical stage, hundreds, indeed thousands, of these names find their way into this richly impressive tome.

The era of the afore-mentioned Godfrey O’Donnell, who perished at the Battle of Ath Thairsi in 1258, highlights this and other civil conflicts of subsequent times. Here, too, we have the Battle of Farsetmore (1567) and the Battle of Scarrifhollis (1650). The late Patsy O’Donnell, former Urban Councillor, was a solid voice in times past calling for much more recognition of these events in local schools – he would undoubtedly thoroughly approve of the opening chapters of ‘Where the Winding Swilly Flows’.

And what about the Battle of Sprackburn (July 12th, 1822) when a group of marching Orangemen from Milford clashed with the Catholics of Letterkenny near Gortlee – an altercation that threatened “to spill into terrible bloodshed” only for the intervention of local cleric, Fr James Gallagher?

Other battles fought much further afield also merit a chapter, not least the First World War when 91 soldiers from Letterkenny died and are now remembered in the recently erected memorial at Cathedral Square. The War of Independence and the Civil War saw arms raised and ammunition fired – Constable Albert Carter shot dead by a revolver bullet to the throat following an attack on the Main Street on Wednesday May 18th, 1921, after a patrol of three constables and one sergeant came under fire from local representatives of the 1st Northern Division at McGlynn’s Walsteads near the Literary Institute.

That attack prompted swift reaction from the Black and Tans and local men, Anthony Coyle and Simon Doherty, were injured when McCarry’s Hotel was “fired up and a grenade thrown through the window”. Even when the R.I.C. vacated their barracks on March 28th, 1922, there was still tragedy. A group of young boys came upon a stockpile of explosives which had been dumped over Port bridge. But they had lodged in silt and were easily uncovered and, as a result, James Moore, from Rosemount, was tragically killed as he and his friends played football with one of the devices.

During the War of Independence, the author reveals, arms were hidden under the heating chambers of St. Eunan’s Cathedral. To the knowledge of the clergy of the time we do not know.

But this is not a history devoted simply to war and victims – for there are many chapters detailing the growth of the town and its development as a commercial hub, not forgetting – and it appears very little has been forgotten in this extensive trawl through Letterkenny’s history – the spiritual, sporting and cultural progress of the town.

That economic growth owed much, the book tells us, to the development of the Port and the Railway. Prominent local businessman William George McKinney – not, as the author points out, to be confused with the Oatfield McKinneys – bought the Port in 1900 and for many years held the contract for supplying St Conal’s Hospital with 12,000 tons of steam coal. Ten years after McKinney’s death, A.D. Kelly, son of Charles Kelly who had attempted to purchase it forty years previously, acquired the Port from Cecil McKinney – the Kelly family establishing an import business that brought ships from England, Scotland, Poland and Holland into Letterkenny.

By the 1960s those days were numbered and in 1980, the Scottish ship, Polarlight, arrived with a cargo of salt and “sailed off into history as the last boat to use the Port at Ballyraine.”

The railway system is given its due recognition as it played such a key role in Letterkenny’s development. The last Stationmaster at the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway was Rory Delap while his counterpart then in the County Donegal Railway was Matt Patterson.

In keeping with the author’s consistent departure into additionally enlightening information, the reader learns that Mr Delap was the grandfather of the former English Premier League football of the same name (the younger Rory also mentioned elsewhere) and Mr Patterson was the father of the well known, Pattersons folk group who, as another chapter of the book relates, featured in a residency on the Morecambe and Wise Show on the B.B.C.

Education, too, features prominently, and we read of a Primary School in Oldtown in 1836 where 43 children were registered and the teacher was Mr Hamilton Duggan; and another establishment at Drumminny where the teachers included John Wilson – much too early for the future Minister for Education even if the latter did, many years later, teach in St Eunan’s College – and Ellen Russell.

One illustrious student opened by Dr Crerand was George Sigerson from Strabane who spent a year there in 1850, before going on to become a renowned poet, scientist, letter writer and politician. Due to “alleged sectarian trouble” in the area, young George’s parents had relocated him to Paris where, ironically, Dr Crerand had made the reverse journey to Letterkenny because of “an increase in revolutionary activity” in the French capital. Sigerson is better known in the modern era given that a well acclaimed Gaelic football trophy is named after him.

Industrial development gets its airing and there are many citizens of the town, past and present, who owe thanks to the Oatfield Sweet Factory, Lymac’s Bottling Store, the Hosiery Factory and the Bacon Factory, among many others, for their livelihoods. Sadly, like the original Courtaulds (later UNIFI Textured Yarns Ltd.) they have all passed into history and, naturally, into this book.

Politics and religion have chapters as does the cultural quarters of the town from the days of the scraping chairs in the Convent Hall to the advent of An Grianán Theatre. And no such publication would be complete were sport to be left on the sidelines and everything from the first recorded football match in the town which brought the Friendly Club and the Town Club together for a nine-a-side tussle on January 30th, 1882, to Mark English’s bronze medal triumph in the European Athletics Championships in August of this year is covered over twenty-two invigorating pages.

But, again, it’s the names of those involved in all these categories that the writer puts the focus firmly on.

And for all of its 294 pages, complete with countless images that divide them up neatly, it’s the people who are the lead characters in the drama that is Letterkenny’s evolvement from its days as that small market town to the populous centre of today and one that now boasts a history book worthy of every one of its years.