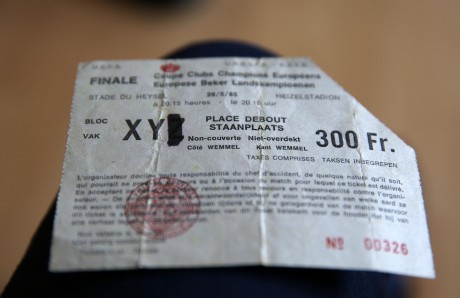

Kevin McFadden holding his match ticket. Photo by Declan Doherty

BY CHRIS MCNULTY

c.mcnulty@donegalnews.com

IT should have been the trip of a lifetime, but now it’s his worst nightmare.

Kevin McFadden left his home at Garshuey, between Newtowncunningham and Killea, for a journey that would end in the Heysel Stadium, Brussels and the European Cup final between Liverpool and Juventus.

Accompanied by regular travel companion, the late Mickey Cresswell from Derry, McFadden flew to Heathrow before getting a train to Dover, the meeting point for the Supporters Club.

On board the bus they were presented with match tickets. As things turned out they wouldn’t need them.

The night of May 29th 1985 remains one of football’s most infamous nights. Thirty-nine fans – 32 Italians, four Belgians, two French fans and 37-year-old Belfast native Patrick Radcliffe, who worked in Brussels as an archivist for the EEC – lost their lives and 600 more were injured after disturbances broke out in Section Z, a supposedly neutral area in the dilapidated Heysel Stadium that night.

Supporters in the Liverpool end charged through the chicken wire dividing the sections, manned by a flimsy line of police officers.

As Juventus fans sought refuge, they attempted to climb the perimeter wall at the corner flag. Some succeeded; others didn’t emerge from the pile-up (six deep in places). The wall eventually collapsed under the siege. Had it withstood the pressure, the death toll could have been even greater.

McFadden was nearby in Section Y. He could sense that something was amiss, even on his approach to the stadium.

“It was mayhem,” he says now, clutching the ticket he was never asked to produce at the point of entry.

“Flagpoles were confiscated at the entry point, but others in the queue were just hurling them back over the wall again. How could that be allowed happen?

“There was a scramble to get in and there were no turnstiles at all.”

Sixteen years earlier, McFadden – whose father, Paddy, was a founder member of Kildrum Tigers – was the PRO at Finn Harps when one of the conditions of their entry into the League of Ireland was that they installed turnstiles at Finn Park (they loaned them from Sligo Racecourse).

“This was the European Cup final,” as he points out.

“I was in better grounds in the League of Ireland. There were 12,000 fans in the area behind the goal where we were.

It was just pure clay in parts, there was rubble lying in others and there were no toilet facilities – you had to pee against a wall and it was just running down past you.

“The game should never have been played there.”

That was a point that had been made by Peter Robinson, then Liverpool secretary, who had pleaded with UEFA to alter the venue. His request fell on deaf ears.

McFadden wasn’t exactly a novice on these trips. Four years previously he was at the Parc des Princes to see Alan Kennedy’s 81st minute goal give Liverpool a 1-0 European Cup final win over Real Madrid.

At Heysel in 1985, over two hours after the scheduled kickoff, the Liverpool and Juventus teams finally took to the field. The heightened tension made for a cutting atmosphere.

Uefa and the Belgian authorities had decided to play the final, with the repercussions of a cancellation bound to see the spillover on trouble onto the streets of Brussels

At section z, Alongside where McFadden stood on section y, there was a clearance from where the wall had collapsed. The only reminder on the decrepit terraces of the manic scenes of late evening being the shoes that scattered silently; Shoes of many of those who were fortune to survive the crush, and shoes of many who didn’t.

A famous image by then Guardian newspaper sports photographer Eamonn McCabe, of the 1985 Heysel stadium crush. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe.

McFadden, now 70, recalls that day, 30 years ago, as if it were yesterday. He says: “It was painful to watch the match knowing that so many people had died. We were thinking: ‘Is there worse ahead?’ ‘Are we trapped?’

“Imagine if their fans had all been out of the ground before us…there could have been hundreds dead. It was frightening. You were just fearful for your own safety.

“You have time when you’re standing for two hours to think about it all.

“There was a sense when it kicked off that we shouldn’t be the winners of the game. That was very evident. We were just shy of cheering for Juventus.”

Years later, Alan Kennedy relayed the opinion that ‘we could not win the match’. They didn’t. In the 56th minute, Michel Platini scored a penalty after Gary Gillespie’s foul on Zbigniew Boniek was deemed to have been inside the penalty area by referee André Daina. Gillespie’s challenge was a yard outside. There were few complaints in the circumstances.

McFadden says: “If Liverpool had won the game that would’ve been even more fatal.

“That would’ve meant that the Italians would have been out of the ground first and would have been waiting on us.”

With the majority of the Juventus hoards staying back to see Gaetano Scirea, their captain, lift the cup, Liverpool’s fans were ushered back to their transport.

Then, a moment that visibly shakes McFadden to this day: “We were just sitting there, back on the bus and ready to leave and this brick shattered the window beside me. It was terrifying.”

They were anxious times, too, for friends and family back at home.

“The mother had Padre Pio, The Sacred Heart, St Oliver Plunkett and everybody along with him,” says McFadden’s sister, Carmel.

Some swore they’d seen him falling over the wall in the crush as they viewed the horrific pictures on television.

He worked in the Everglades Hotel in Derry and when back at their hotel each member was allowed one phone call. He called the Everglades and word filtered home that he was safe.

Their base was the Hotel Princess in Ostend, sixty miles from Brussels. McFadden’s memories are vivid. The night before the game they enjoyed a meal, washed down with a bottle of St Emilion ’78, in the Le Mirabeau restaurant.

The morning after the game, the reception was very different.

“They just threw the breakfast at us and wanted us out of the place,” he remembers.

“Travel arrangements meant nothing the next day – we were just ordered out at half seven. Everything was changed. It was like a total blackout. The hotel basically shut down when we got back – there was no food, no drink, no nothing.

“At the ferry in Calais was like a scene from The Spy Who Came In From The Cold with the Alsatians marching us in from the bus onto the ferry.

“We were treated like hooligans. It was as bad when we got back into Dover.”

Kevin’s match ticket.

The weekend prior to his departure, he attended the wedding of Shaun and Frances Watson.

Upon his return, he was afforded a round of applause in the Carrig Inn, Alma O’Donnell’s watering hole in Carrigans.

The image of Anne Diamond, presenting Good Morning Britain on TV-am, “with an aggressive face blaming us for what had happened”, still grates with McFadden, convinced that members of The National Front were to blame.

“I heard her saying: ‘The Liverpool fans ran riot’. That was sickening. “The people who were in the area who shouldn’t have been there should have been interviewed and asked what happened.”

Last year, while accompanying the Killea FC Academy on a trip, he attended the Stoke City v Newcastle United game at the Britannia Stadium, a 27,743-all-seater stadium with a family stand and even working toilets – changes brought about by tragedies such as Heysel.

Thirty years on, he’s never seen his beloved Liverpool in the flesh since that fateful night in Brussels, content instead to toil with Killea FC.

“I couldn’t go into crowds,” says McFadden, who worked as a Front of House Manager at the Everglades.

“If there was a wedding on, I’d have had to be in the room all day before they came in. I couldn’t walk into a crowded room after Heysel. I was never like that.”

May 29 1985 changed it all: “Heysel, for me, was the night football died.”

Kevin’s coach pass issued by the Liverpool FC Supporters Club.